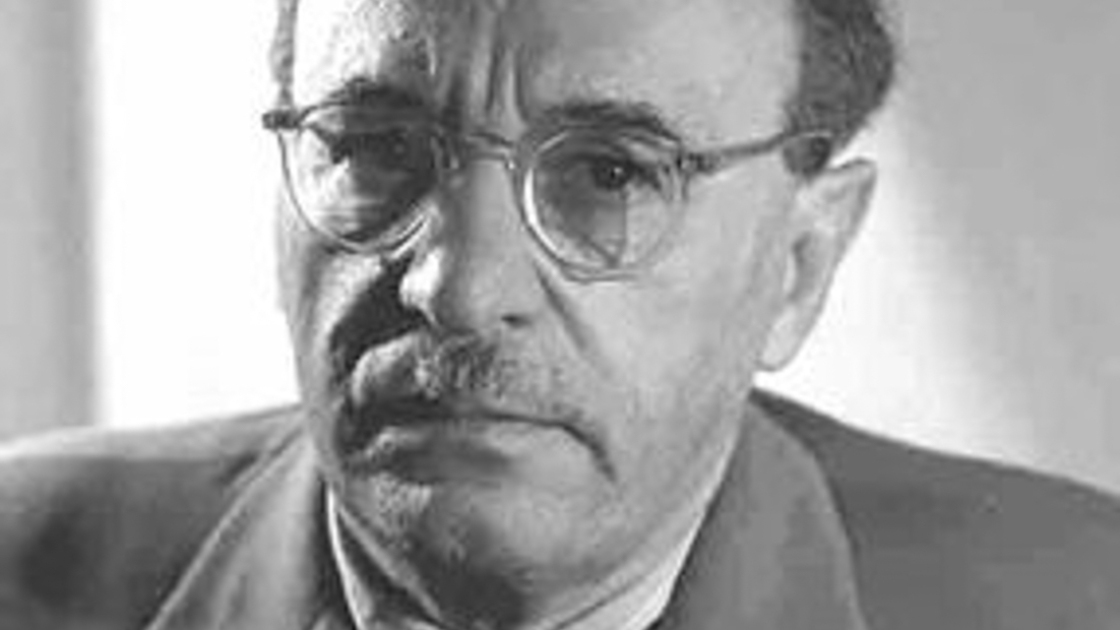

Shneor Zalman Rubashov was born in 1889 in the Belorussian town of Mir. As the son of a Hassidic family of rabbis, he was educated in a Talmudic academy. He eventually changed his name to Zalman Shazar. During the 1905 revolution, he joined a Zionist movement and rapidly became active in assembling self-defense forces in Belarus and Ukraine. At age 18, he was accused of revolutionary activism and journalism and arrested by Tzarist forces.

Shazar’s first visit to Israel was in 1911, but at the outbreak of the First World War, he was living in Germany working as a journalist. In 1920, he married fellow Belorussian Rachel Katzenelson, whom he had met in St. Petersburg at the Academy for Jewish Studies. He was prevented from leaving Germany until 1924, when he immigrated to Palestine. During British occupation, he worked for the Zionist Labor Organization and was editor of the Hebrew-language daily newspaper Davar.

He rose to chairman of the Zionist Executive and chief of the World Zionist Organization’s Department for Education and Culture. By 1947, he had become a member of the Jewish Agency delegation to the United Nations General Assembly. He was one of the drafters of Israel’s Declaration of Independence.

In February 1949, Israel’s parliament, the Knesset, was established. “The Knesset took its name and fixed its membership at 120 from the Knesset Hagedolah (Great Assembly), the representative Jewish council convened in Jerusalem by Ezra and Nehemiah in the 5th century b.c.” (Jewish Virtual Library).

Zalman Shazar was elected as a member of the first Knesset and as the country’s first minister of education and culture, where he served until 1951. The following year, he became a member of the Jewish Agency Executive; he was appointed as acting chairman of its Jerusalem Executive from 1956 to 1960. In 1963, the Knesset elected him as the third president of Israel—he won a second term in 1968.

In September 1968, a proposal by two teachers of Ambassador College was presented to its founder Herbert W. Armstrong. The aim was to conduct an archaeological project a few miles north of Israel’s capital, Jerusalem. He sent two officials to Jerusalem to investigate if permission would be granted by Jewish authorities.

At the time Prof. Benjamin Mazar, archaeologist and former president of Hebrew University, was leading what Mr. Armstrong termed “the most important ‘dig’ so far undertaken, starting from the south wall of the Temple Mount. Three major United States universities had sought participation in this outstanding project. All had been rejected. But Professor Mazar offered a 50-50 joint participation to Ambassador College!” (co-worker letter, May 28, 1971).

This project was infinitely more significant than that which was first proposed. “However, about mid-October [1968] I did fly to Jerusalem to look over this project. The ‘dig’ had been begun a few months before. I met Professor Mazar and inspected the project. It was much more impressive than I had expected. I began to realize the scientific and educational value to Ambassador College. A luncheon was held in a private dining room in the Knesset, the government’s capitol building. Present at the luncheon were five high-ranking officials of both the university and the government.

“It was a most memorable luncheon. The favor we were given in their eyes, the warmth of their attitude toward us, was inspiring, astonishing and most unusual. The Israeli minister of tourism and development, Mr. Moshe Kol, proposed that we build an iron bridge that could never be broken between Ambassador College and Hebrew University. After 2½ years that ‘iron bridge’ has been greatly strengthened.

“I did not make a final decision, however, at that time. We agreed to meet again in Jerusalem on December 1, for final decision. Meanwhile, Dr. Mazar, with Dr. Aviram, dean of the College of Humanities at the university, came to Pasadena, and visited also the Texas campus, to look us over. They liked what they saw. And on December 1, at the official residence of Israel’s president, Zalman Shazar, we made the joint participation official” (ibid).

“Do you want a formal, legal contract?” I was asked. “My word is good,” I replied. “And I believe yours is, too, without any legal entanglements.” That was good enough for them, and our friendship and mutual participation has grown ever since” (co-worker letter August 19, 1976).

Ten days after this meeting with President Shazar, Professor Mazar and Dr. Aviram, both Polish immigrants, now together crossed the Atlantic Ocean to America to visit the Texas and California campuses of Ambassador College and address faculty and students regarding the Jerusalem archaeological excavations.

Mr. Armstrong readily admitted that it was not until after stepping out in faith that he learned that this epic archaeological project contributed directly to the clearing of rubble and debris where Jesus Christ is to return (Isaiah 9:7).

So motivated was Mr. Armstrong by this new phase of God’s Work, that between 1969 and 1970 even Israeli Army Gen. Yigal Yadin was referring to his trips to Jerusalem as “monthly visits.”

Mr. Armstrong’s historic meeting with President Shazar took place at the home of the president, which acted as both residence and palace. The president saw the need for a residence to be constructed in Talbiya, one of Jerusalem’s suburbs. Famed Israeli architect Aba Elhanani was chosen to design the Beit HaNassi, Hebrew for President’s House.

The residence consists of three wings: the ceremonial, offices and residential. The home features Jewish artwork, while its gardens were landscaped to feature native olives, oak and cypress trees. President Shazar inaugurated Beit HaNassi in 1971, and called it home until he left office in 1973.

That same year, the Historical Society of Israel with the assistance of the government founded the Zalman Shazar Center in honor of its third president.

Almost six years after his meeting with Mr. Armstrong, Zalman Shazar died in Jerusalem on Oct. 5, 1974. Mr. Armstrong would frequently refer back to that initial meeting with President Shazar as the first head of state to meet with him. That meeting began a 17-year period of God’s gospel message being delivered in person to world leaders fulfilling Christ’s prophecy found in Matthew 24:14.

As evidence of the continuation of the iron bridge between the unofficial ambassador for peace and Judah, one month after the death of the third president of Israel, his successor, Ephraim Katzir, received Mr. Armstrong at Beit HaNassi before touring the archaeological excavations in Jerusalem. The big dig would continue as would the delivery of the good news of the coming Kingdom of God and the ultimate establishment of His throne in Jerusalem.

“He shall be great, and shall be called the Son of the Highest: and the Lord God shall give unto him the throne of his father David: And he shall reign over the house of Jacob for ever; and of his kingdom there shall be no end” (Luke 1:32-33).

For more information about the modern day continuation of the archaeological iron bridge between Israel and Herbert W. Armstrong College, visit www.keytodavidscity.com.