At first glance, Martin Van Buren embodied everything Andrew Jackson disliked. Van Buren was every inch the “complete politician.” Known for his eloquence and charm, he effortlessly won people to his side without drawing attention to himself, earning him the nickname “the Magician.”

Military hero Andrew “Old Hickory” Jackson did not like magic. He hated corrupt politics and backdoor deals among officials. He was frank, practical, up-front and naturally suspicious of politicians like Van Buren.

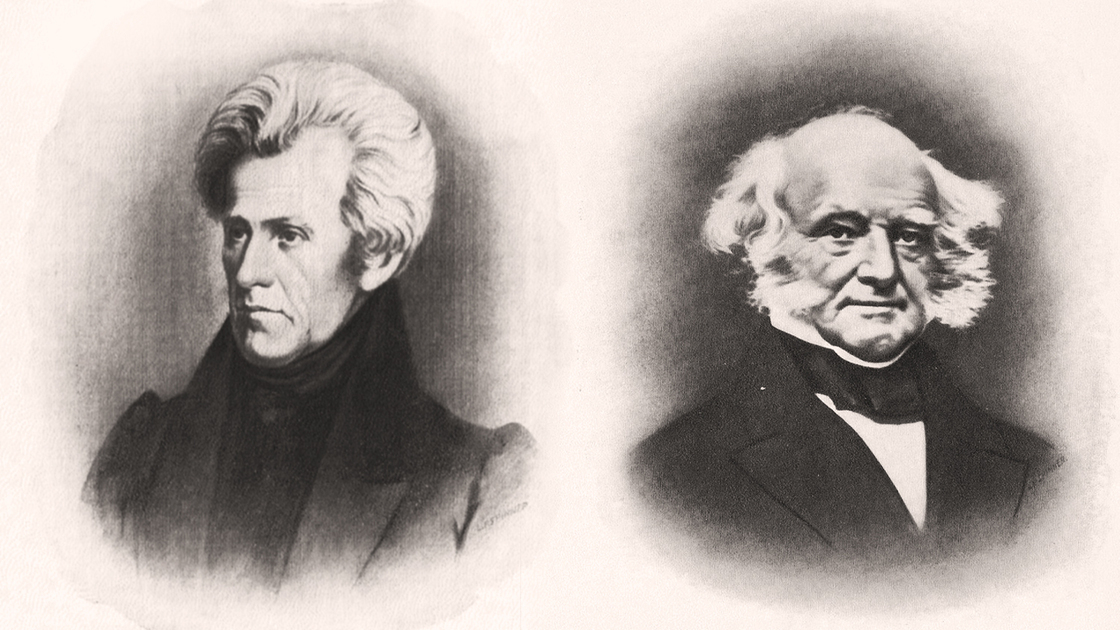

Standing an inch over six feet, Jackson’s angular frame was punctuated by steely blue eyes that flashed with intensity when he took the floor in the Senate. Van Buren was more diminutive, both in physical stature and personal conduct. Five-feet-six-inches tall, he rarely raised his voice and possessed extraordinary composure. He was stoic where Jackson was animated. While Jackson thrived on direct interaction with a doting public, Van Buren preferred to be the man in the background, quietly pulling the strings. Yet they did have one thing in common: Neither of them could have predicted what the presidential election results of 1824 would mean for their political and personal futures. This election would determine who would be the sixth President of the United States.

Already a beloved, well-known military hero and senator for Tennessee, Andrew Jackson easily carried the support of most of the western states and several southern ones. His most serious rivals in the race were John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay and William Crawford—the candidate Martin Van Buren supported.

To put it in modern terms, Van Buren was Crawford’s campaign manager. He led a pro-Crawford group in Congress called the Radicals, the most conservative wing of a divided Republican party (the only political party at the time). He thought Jackson was unqualified to be president, calling him a “military chieftain.”

Andrew Jackson swept the popular vote, with John Quincy Adams coming in second place. But although more people voted for Jackson than Adams, Jackson didn’t have enough electoral votes to be inaugurated, so the decision lay with the House of Representatives.

After some shady political maneuvers—including Henry Clay promising all his electoral votes to John Quincy Adams in exchange for being made his Secretary of State—Adams was elected the sixth president by the House of Representatives. Thanks to Clay, Adams beat Jackson by one electoral vote.

When he learned of Clay’s appointment as Secretary of State, Jackson collapsed and moaned: “I shudder for the liberty of my country.” Van Buren shared his dismay over the 19th-century edition of a “stolen election.” Both were astonished that the will of the people had been so casually overruled.

In reaction, Jackson decided to form a new political party in opposition to the Republicans. This party would believe in a strict interpretation of the Constitution and a limited central government bound by the will of the people. He wanted a return to “democratic” values. But Jackson couldn’t form this new party alone. He needed a wise counselor—someone with political clout who could work “magic.” He needed Van Buren.

Thus began one of the unlikeliest alliances—and friendships—in American history.

Over the next few months, Van Buren began aligning himself with these “Jacksonian” ideas, officially casting his support to Jackson’s new Democratic party in late 1824. Van Buren became the “campaign manager” for his former rival!

Throughout these “campaign years,” Jackson’s opinion of Van Buren slowly shifted from one of disapproval to appreciation. Writing to a friend, Jackson said, “I have found [Van Buren] everything that I could desire him to be …. Instead of his being selfish and intriguing, as has been represented by some of his opponents, I have ever found him frank, open, candid, and manly. As a counselor he is able and prudent, republican in his principles and one of the most pleasant men to do business with I ever knew.”

When he ran again in 1828, Andrew Jackson was elected the seventh President of the United States by an overwhelming majority. And his Secretary of State was none other than Martin Van Buren.

The respect began deepening into friendship soon after Jackson’s arrival at the White House. Their first meeting lasted hours longer than it was intended to. Van Buren was initially worried that old tensions would stunt the conversation, but was surprised by Jackson’s “affectionate eagerness” at having him there at last.

For his part, Van Buren developed a high regard for his new superior, going from calling him a “military chieftain” unfit for the presidency to calling him the “greatest politician and statesman” in the nation. When Jackson ran for a second term, Van Buren was promoted from his Secretary of State to his running mate and served as his Vice President from 1833-1837. At the end of Jackson’s tenure, Van Buren continued his legacy, becoming the eighth President of the United States.

When Andrew Jackson left the White House, Martin Van Buren was by his side and helped him into his carriage. Once dubbed “two of the most unlikely of allies in American political history,” these two men had definitely “revised” their first impressions of one another. Not only had they resolved their differences, they had formed a new political party together, served for eight years together, and grown to deeply respect and support one another—despite the fact that they used to be enemies.

Based on appearances and first impressions alone, it would have been easy for Jackson and Van Buren to assume they could never be friends. Instead, they each put aside their differences for a common goal and built a friendship that lasted the rest of their lives and brought each of them heightened success.

Christ’s admonition in John 7:24 rings true: “Judge not according to the appearance, but judge righteous judgment.” First impressions can sometimes be wrong and based on hasty assumptions—just as Jackson assumed Van Buren was automatically corrupt because he was a politician, and Van Buren assumed Jackson had no presidential qualities because he had no political training. Time proved both assumptions wrong.

Had these men not been big enough to put aside their differences for the good of the nation, they might never have forged such a rewarding partnership. Had they not taken the time to judge each other by their fruits rather than what other people said about them, they might have assumed that all the negative rumors they heard were true. Instead, they approached each other with open minds and mutual respect, and discovered that they were well-suited complements.

Jackson and Van Buren both made sure to express their appreciation and praise each other’s strengths to their other friends. They still disagreed sometimes, but they always talked through those disagreements until they reconciled. At the end of the day, they knew they had each other’s backs.

Often, the people you don’t get along with at first turn out to be some of your best friends! They don’t need to have the same likes and dislikes to be a close friend. Jackson and Van Buren’s differences actually strengthened their friendship rather than hindering it. Without Van Buren’s political ties and experience, Jackson could never have enacted his reforms so efficiently. And without Jackson’s support, Van Buren might never have served as America’s Commander-in-Chief.

Building friendships, relationships and partnerships—especially with people you don’t “click” with right away—isn’t easy. It requires a determined effort on both sides. The alliance and friendship between Jackson and Van Buren never would have worked if only one of them had put forth effort. Van Buren had to know that Jackson respected and valued his opinion, and Jackson had to know that Van Buren would always support his decisions. Because they both decided to give an alliance a second chance, they succeeded. Behind an “enemy,” they found an ally. And even better, they found a friend.